Psychodramaturgie Linguistique (PDL, in English Psychodramaturgy for Language Acquisition, in German Sprachpsychodramaturgie) is an approach to foreign language acquisition that has been developed by Marie Dufeu and myself since 1977. The name refers to the two specific main sources: psychodrama and dramaturgy. However, PDL is neither a therapeutic(1), nor a theatrical method. We do not provide theatre and we do not do theatre.

In the text "Pedagogy and Therapy"1 on this website, I tried to clarify the relation to therapy; the reference to psychodrama in the term “psychodramaturgy” called for it. Here I would like to clarify what we mean by "dramaturgy" when we refer to "Psychodramaturgy".

PDL has several points of contact with the world of theatre and actor training:

- the use of neutral masks in the introductory phase of a beginner course2

- J.L. Moreno’s Spontaneous Theater on the creation of spontaneous expression

- the use of exercises from actor training (freeze frames, sculptures ...) as warm-up exercises for main exercises, or as the starting impulse to a main exercise.

- the Forum Theatre technique of Augusto Boal, which has been adapted to foreign language teaching (see Dufeu, 1992, pp. 194-195 and Dufeu, 2003, pp. 199-200).

The dramaturgical aspect of PDL lies primarily in its consideration of dramaturgical principles, which are used in the setting up of exercises and selection of texts. This will be the subject of this article.

We will first outline some of the dramaturgical aspects of PDL.

We will then illustrate the dramaturgical approach of PDL using two concrete examples of typical PDL activities (a projection exercise and an activity on a literary text).

1. The Dramaturgical Dimension of PDL

“Dramaturgy” is often associated to theater due to the word “drama”. In PDL “dramaturgy” is not used in its theatrical sense, but in its structural sense, as in the "dramaturgy of a novel", i.e. the structure, the scaffold, the framework of the action. This is reflected in various features of PDL.

The Concept of Action

“Drama” originally meant "action". We owe the Concept of Action to J.L. Moreno, the founder of Psychodrama. Instead of approaching the acquisition of a foreign language with a textbook, PDL considers the settings (constellations of encounters, e.g., doubling, mirroring3, polarity (see Dufeu, 2003, 180-185), the cushions (see 3.1) ...), situations or documents (texts, images, objects ...) that lead to the encounter and communication between the participants and to the experiencing of the language and further to its acquisition. There is no pre-ordained “target” language. The newly acquired language corresponds to the expressive needs of the participants in the given situation. They acquire the linguistic skills to deal with the moment. Communication arises out of the relation between the participants and from their desire to act in the situation.

The Principle of Resonance

An informative text on "The weather in Switzerland"4 sparks little interest. Text reading will usually lead to comprehension tests, i.e. to question-answer communication, the answers of which can be found in the text and mainly serve to assess the participants’ comprehension of the text. Communication is primarily hierarchical in nature, the "knower" asks the "learner" about content that the first person already knows. The proposed "transfer" into the learners’ reality: "What is the weather like in your home country / favourite country?" cannot be considered very "appealing". The aim of this exercise is to study and learn the vocabulary and the linguistic structures of a certain topic. They are linguistic criteria. This goal focuses on the meta-language function of language at the expense of its essential functions: the expressive, communicative and symbolic functions; these essential functions can arouse a much deeper resonance among the participants.

The principle of resonance can already be found in ancient Greek theatre, which dealt in particular with social and human issues that directly or symbolically addressed the audience. This means that in order for the Action (the Drama) to reach the audience, an identification or a desire to react must be potentially available.

In PDL we choose a document (text, image ...) not based on its vocabulary or linguistic structure, but on the basis of its direct or symbolic resonance potential for the participants. Before we decide on a text or an image, we analyze the topics that are apparent or that resonate subliminally so that the participants feel addressed, i.e. feel an inner resonance and develop the desire to react to the document (see §3.2. below).

The Principle of Dramaturgical Forces

We mainly refer to Emile Souriau's work: Les deux cent mille situations dramatiques5. The development of a dramaturgical plot is carried by the dynamics of forces or functions. Souriau identifies six possible forces that can be found in a drama.

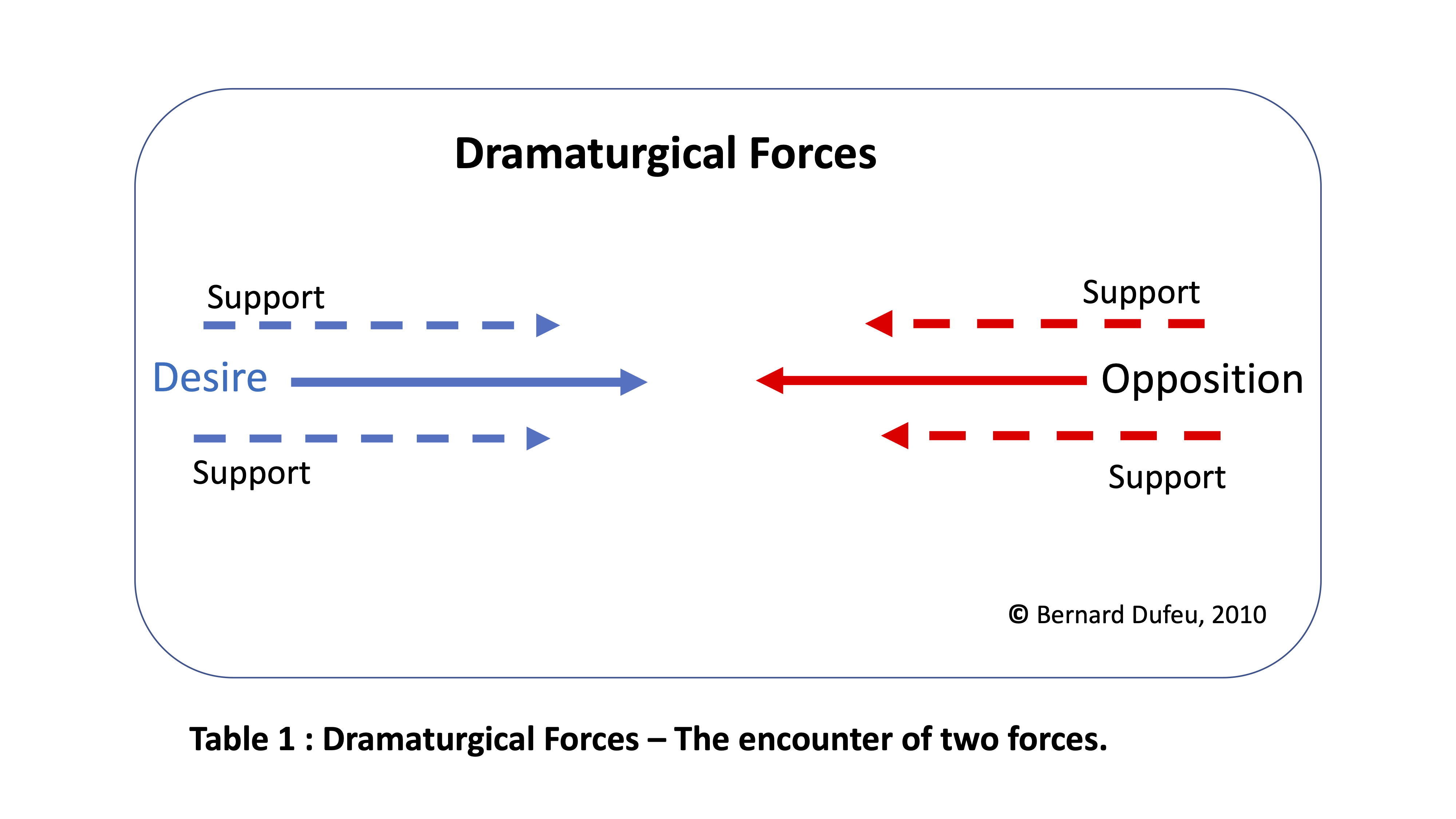

Of the six forces Souriau suggests for analyzing dramas, three seem particularly important to us. We have developed a terminology for these forces that is better adapted to the educational context: the Desire (for Souriau it corresponds to the Force thématique orientée), the Opposition (L’Opposant), the Support (La Rescousse).

These forces are not fixed or tied to one persona; they can in the course of the drama change, jump over to others, or even be replaced by other forces.

The dynamic of a situation arises from and is further developed by an imbalance in the distribution of these forces or from the displacement or disappearance of a force.

To illustrate the interplay of these dramaturgical forces and understand better the dramaturgical principles on which PDL is based, we briefly put ourselves in a classic dramaturgical situation.

A girl loves a boy; he loves her; their parents agree to the marriage. End of story. Although it is a wonderful situation, dramaturgically speaking, it is flat, because all forces go in the same direction.

But if we assume that the girl's father wants his daughter to marry a rich, old man instead of the boy, then a dramaturgical action will develop in which two main forces are opposed: one purposeful force (desire), one opposing force (opposition) and possibly supporting forces on each side (support from other figures).

This doesn’t only happen to be a piece by Molière, "L’Avare" (The Miser), it also represents the foundations of the dramaturgic action. In the context of language acquisition, the desire to express oneself is promoted by the meeting or crashing of these forces.

Let us now take a concrete example to illustrate the use or consideration of these forces. There is an exercise in PDL called “Polarity”6. Here is a brief outline of the exercise:

After a warm-up exercise with the whole group, in which the participants create short dialogues with only four terms, namely "yes, no, I, you", two protagonists meet in a dialogue that initially only consists of "yes" and "no". In a second attempt, after a few “yes” or “no”, depending on the chosen intonation or mood, one of the protagonists can replace his “yes” or “no” with a verbal expression that occurs to him spontaneously7. The other protagonist then reacts to this statement and a dialogue arises between the two. In this phase of verbal communication, they are both supported by other participants and the trainer. The situation can be represented as follows:

It is not that the protagonist who said “yes" is automatically making a positive statement or that the "no-sayer" is saying the opposite; it is a warming-up that sets forces in motion which then take their course; whether positive or negative.

After one or two encounters have taken place following this scheme, the two new protagonists may decide on two "po- larities" that occur to them before the start of their sequence, e.g. B. "sun and moon" or "big and small", "strong and weak", "lamb and wolf" etc.

In later activities we come to more nuanced forces, which are no longer based on the antagonistic principle of polarity, but are powered by difference (see the example "The cushions" below).

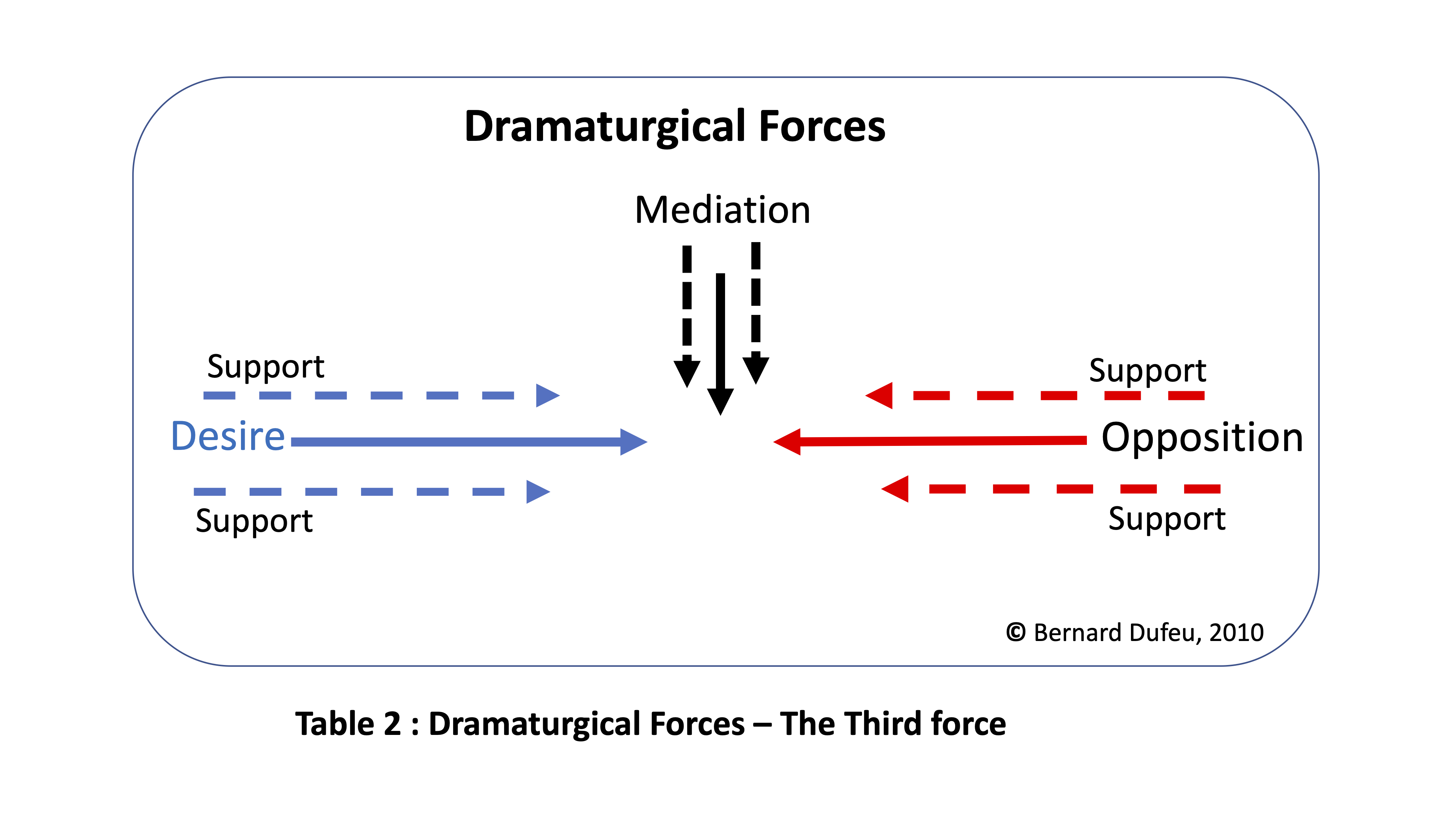

In some exercises we let a third force work, Mediation (in Souriau: “l’Arbitre attributeur du bien”). Sometimes this third force appears in the initial setting, e.g. in an exercise called "The Interpreters", or it appears in a second "act" after a first encounter between two protagonists, to help find a solution to an existing problem or to help make a decision. Then we have the following constellation:

When setting up exercises and / or selecting texts, the presence of these forces is taken into account. If we use text or an image, these forces can be within the document (see Molière's example above) or the document contains a force and the reader who disagrees with the content (opposition) or has a different opinion (difference), forms an opposite force.

We will illustrate these dramaturgical aspects with the help of a projection exercise (the Cushions, see under 3.1.) and with a literary text ("The Return of the Prodigal Son" by André Gide, under 3.2.).

2. The practical access to the foreign language in PDL

In the beginning of a course for beginners the participants take their first steps in the foreign language individually; in the doubling and mirroring exercises (see course description on this websit8 ); they then proceed to encounters in pairs. The next activities lead to group dramaturgy; meaning all participants can then participate directly in the event.

The trainer provides an open framework activity based on projective, associative or situational principles, that should arouse or stimulate the participants' expressions9 .

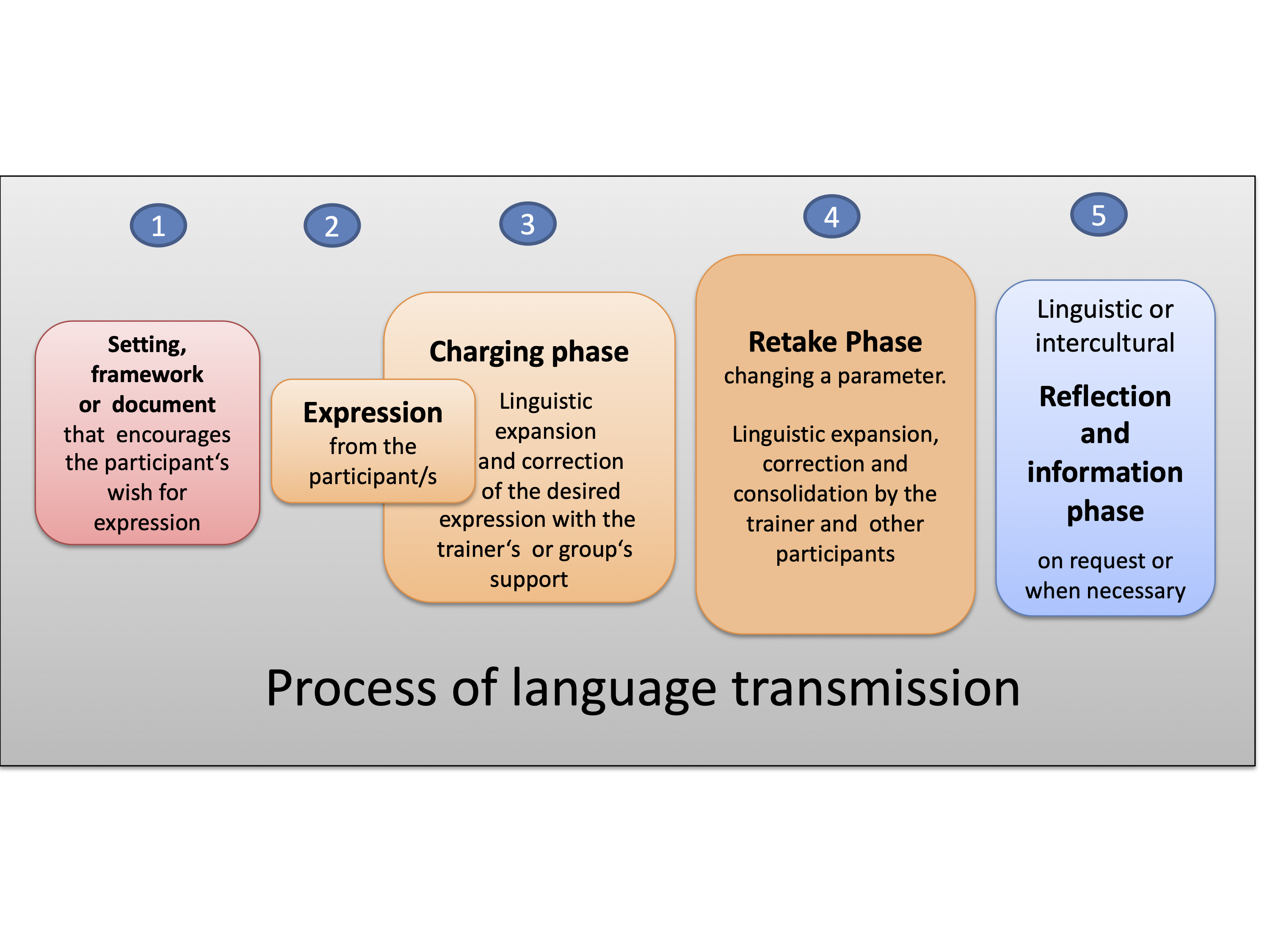

PDL group-activities generally follow this progression:

Starting from a framework-activity (1) which gives the participants and the group a framework for expression to and stimulates their desire for expression, the participants express themselves more or less fluently, correctly or not, in an expression phase (2) during which they are supported by the trainer.In the charging phase (3) the trainer offers the participants a correction, a reinforcement and a linguistic expansion of their expression.

This is followed by the Retake Phase (4) in which a parameter of the situation is changed. In this phase new language contributions are proposed, thus broadening their expression and facilitating their integration. These techniques also stimulate the participant's imagination as they also possess warming up properties.

The Reflection Phase (5) occurs when participants start asking questions about corrections or the trainer considers some explanation to be useful.

We will illustrate these five steps using the exercise “the cushions”10.

2.1. The projection as a trigger for a dramatic situation: the cushions?

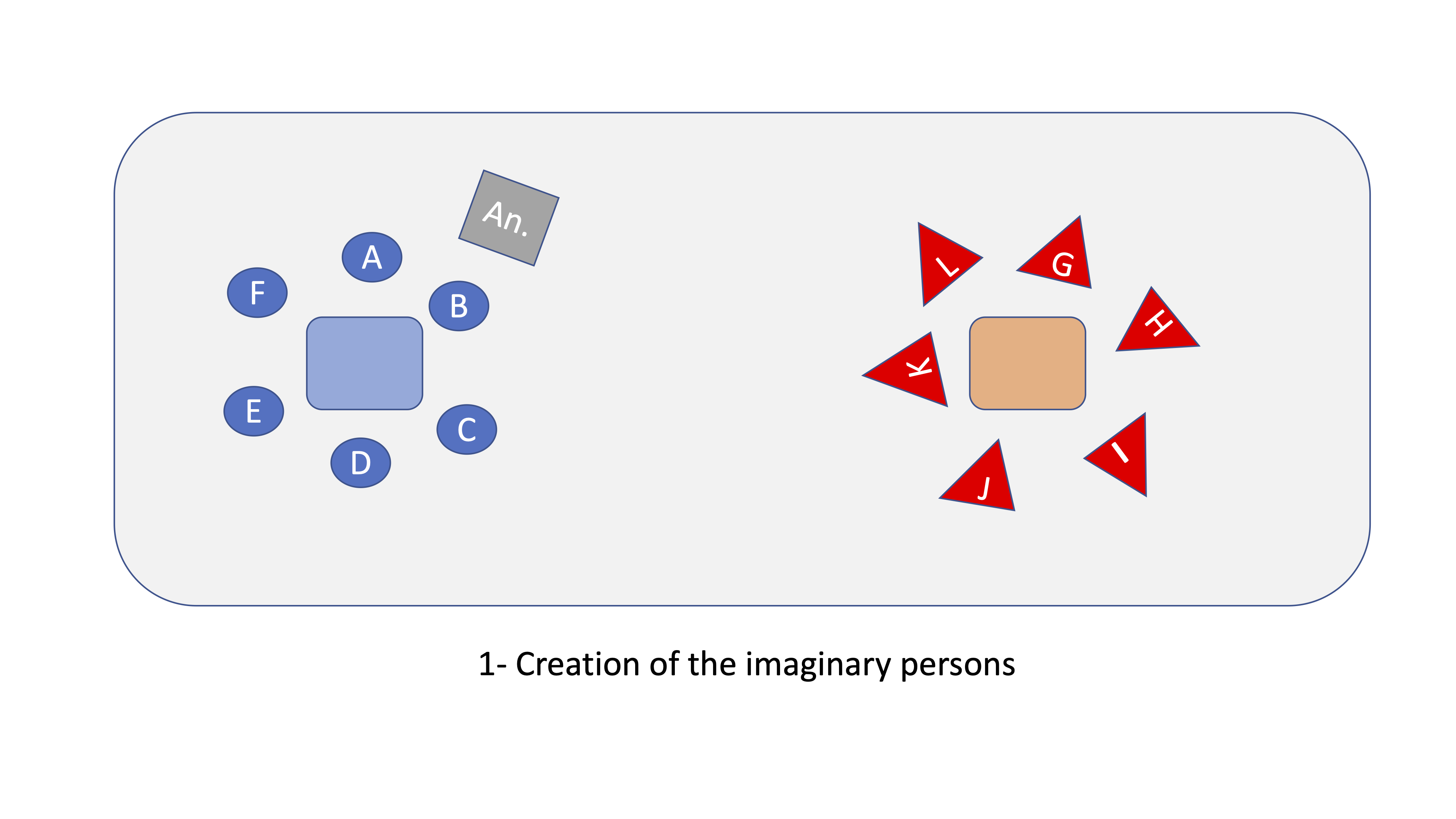

The Cushions exercise is based on a group projection; the creation of two imaginary persons11. Two protagonists in the role of the imaginary person encounter each other and a dialogue ensues with the support of the group. Then, using a special PDL technique, known as the shift, the other participants also take over these roles leading to new encounters with new partners - thus involving all participants. Splitting the group into two sub-groups contributes to the development of two dramaturgical forces that then meet each other. The separate activity of the two groups and the creation of two imaginary persons contributes to the build up of dramaturgical forces that are based on the Principle of Difference.

The themes developed by the group very often have a deeper symbolic significance for the development and the dynamic of the participants and the group, which is why this exercise produces strong forces. Since the imaginary persons stem from the imagination of members within the group, it is the whole group that is jointly responsible for the development of these persons. This makes it easier for the group members to identify with the protagonists representing the invented persons, to support them or to take on their roles in another phase of the exercise, the “shift phase” (see step 6 below), and finally to adapt and also bring in their own ideas.

Warm-up exercise: Tit for tat12

Most of the main exercises in PDL begin with a warm-up exercise that prepares for a technical aspect, attitude or stance that plays a role in the main exercise. Here we use an exercise in which two sub-groups face each other in two rows and react to each other, first expressing themselves only using body language, then with body language and sounds, and finally verbally (first in sentences and then in short dialogues)13.

STAGE 1

2.1.1 - Creation of the imaginary persons (group projection)

Two cushions or two chairs are placed on the opposite sides of the room. The participants are divided into two sub-groups around these two cushions / chairs.

The participants in each sub-group should now project an imaginary person sitting on this cushion / chair. This person will take shape through the input from the group members. The participants can let their imaginations run free, there is only one rule: "The first suggestion applies!" No suggestion may be changed by other group members. This creates a person that every member in the group has helped shape.

Then each group determines which participant from their own group should take on the role of the imaginary person. The selected participants (e.g. A in the first group, G in the second) take a seat on the cushions / chairs and take on the role of the imaginary person.

STAGE 2

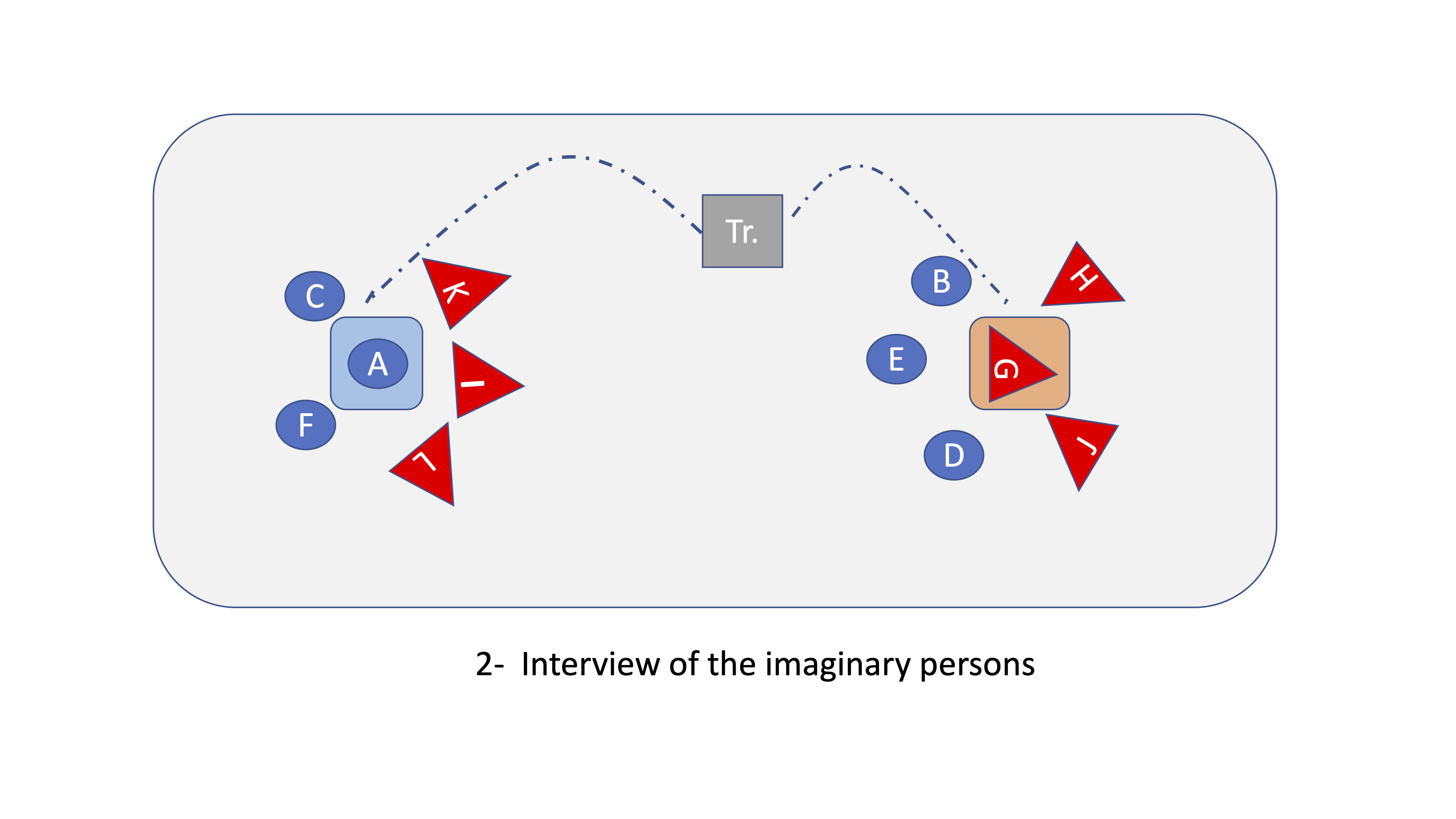

2.1.2. Interview of the imaginary persons

Some participants in group A remain as "supporters" (advisors or relatives of the imaginary person, depending on the context) of Protagonist A and sit behind the protagonists (in the Doubling position) to support him. The remaining participants go over to the other sub-group where the unknown Protagonist G is sitting to interview him as if they were journalists. The same thing happens with the group of G.

of the imaginary person, depending on the context) of Protagonist A and sit behind the protagonists (in the Doubling position) to support him. The remaining participants go over to the other sub-group where the unknown Protagonist G is sitting to interview him as if they were journalists. The same thing happens with the group of G.

2.1.3 Exchange of information

The interviewers go back to their sub-groups and protagonist. For their part, the journalists tell them what they have learned about the other person. The protagonist tells them the new information about himself that has arisen from the exchange during the interviewers in the other group (see table 1)

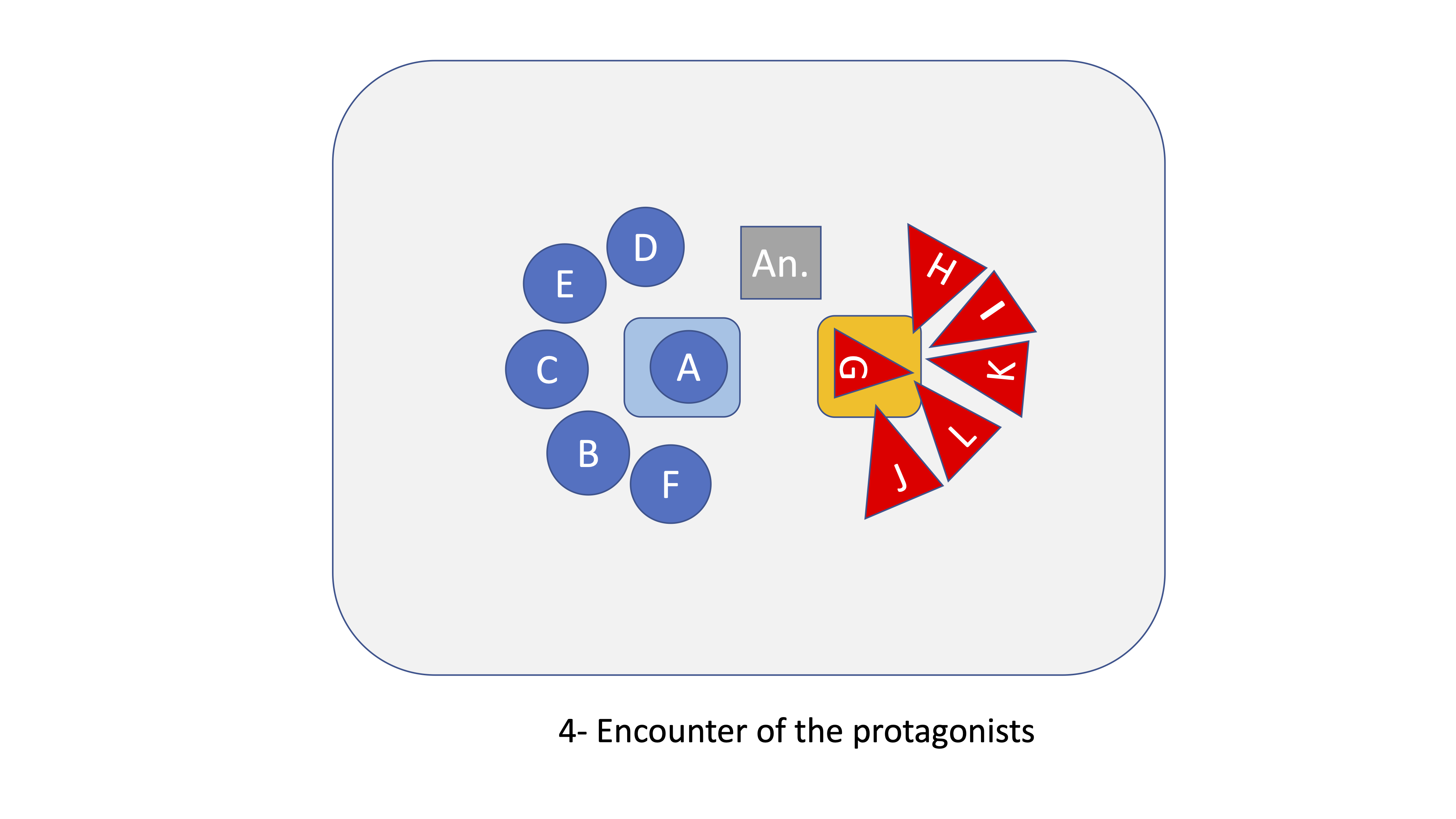

2.1.4 - Encounter of the protagonists

The two cushions / chairs are placed in the middle of the room and the protagonists (here A and G) take a seat on it, their sub-group sits behind them in a semicircle to support them. The trainer sits on the side between the two protagonists. The first encounter / dialogue between the protagonists occurs; their respective sub-groups together with the trainer provide linguistic support.

STAGE 3

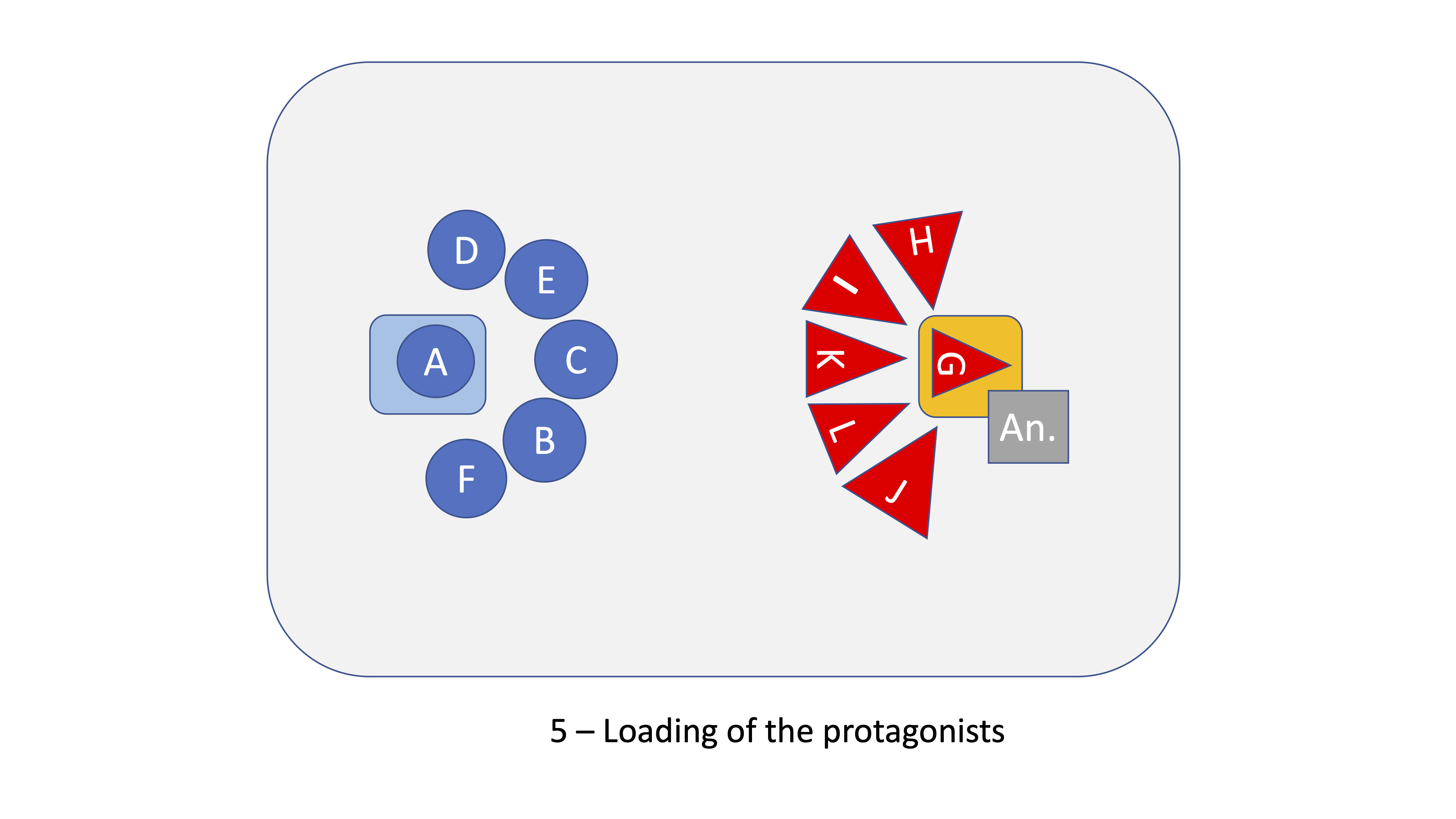

2.1.5 - Charging by the trainer

The two protagonists are then linguistically “charged” one after the other,  whereby the trainer in the doubling position develops and provides a linguistically extended and more fluid sequence of the same content based on the original statements of the respective protagonist14. It offers them synonymous expressions or other formulations (see Dufeu 2003: 233-236). Each protagonist takes over and articulates what appeals to him from the trainer's offer. The latter then adapts her linguistic suggestions to the protagonist's reaction and modifies them if necessary.

whereby the trainer in the doubling position develops and provides a linguistically extended and more fluid sequence of the same content based on the original statements of the respective protagonist14. It offers them synonymous expressions or other formulations (see Dufeu 2003: 233-236). Each protagonist takes over and articulates what appeals to him from the trainer's offer. The latter then adapts her linguistic suggestions to the protagonist's reaction and modifies them if necessary.

STAGE 4

In many communicative activities and in many Drama Education activities or: activities used in Drama Education for instance, one activity follows the other, a linear sequence of exercises is proposed15. The participants indeed have the impression of expressing themselves, but they lack the possibility of reusing the newly acquired linguistic components, which would aid memorization and mastery.

For this reason, in PDL we work with a spiral development within an activity, what we call resumption techniques, whereby some of the new linguistic elements proposed in the previous stages of the activity can be reused in more or less varying situations; thus increasing the participants’ fluency and confidence in the use of the foreign language. We propose "a change in continuity”16; the continuity provides a certain confidence and allows for progress and consolidation, the change prevents the participants from getting the impression of repeating the same thing and enables the newly acquired language to be applied in a slightly modified context. We will illustrate this resumption technique using the "shift" and "double shift" techniques in this exercise.

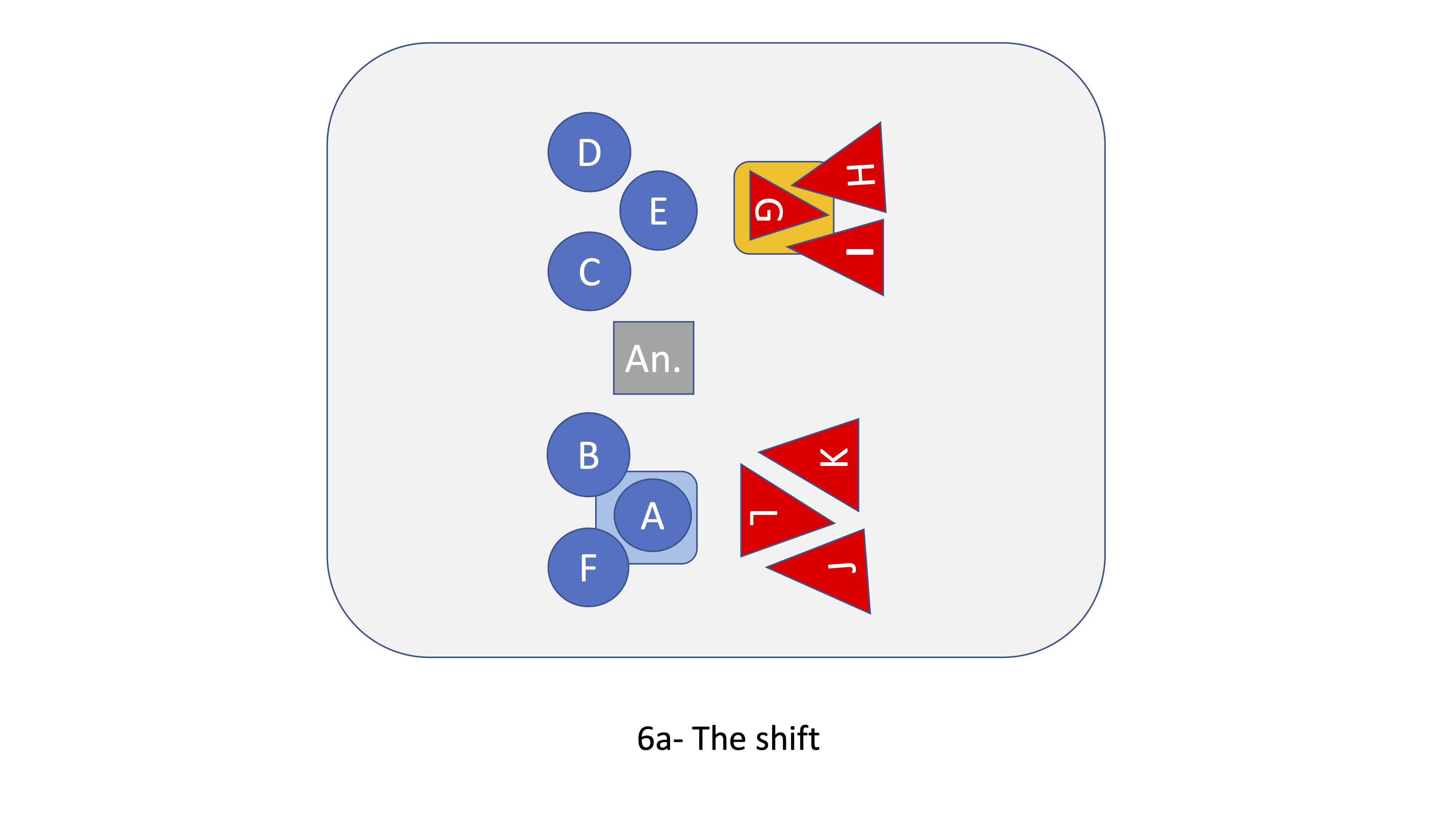

2.1.6 – The Shift

The protagonists (A and G) come back to the centre of the

room - as in stage 4 - each protagonist then moves to the

room - as in stage 4 - each protagonist then moves to the

right by about half a meter, so that each has a free space in front of them, which one participant of the other Group then occupies (E for the group of A, L for the group of G). Two conversations (between A and L and G and E) take place simultaneously, the trainer sits between two protagonists to be able to support all four. The other participants spread out behind the two protagonists of their group. The trainer sits between two protagonists to help the four speakers with the language if necessary, or to correct their expression if it does not disrupt the flow of

two protagonists to help the four speakers with the language if necessary, or to correct their expression if it does not disrupt the flow of

the conversation17.

This shift modifies the original conversation (2.1.4) which also served as a warm-up function for this new conversation, and mostly presents

a linguistic extension of the participants’ expression due to its warm-up function and the charging of the trainer.

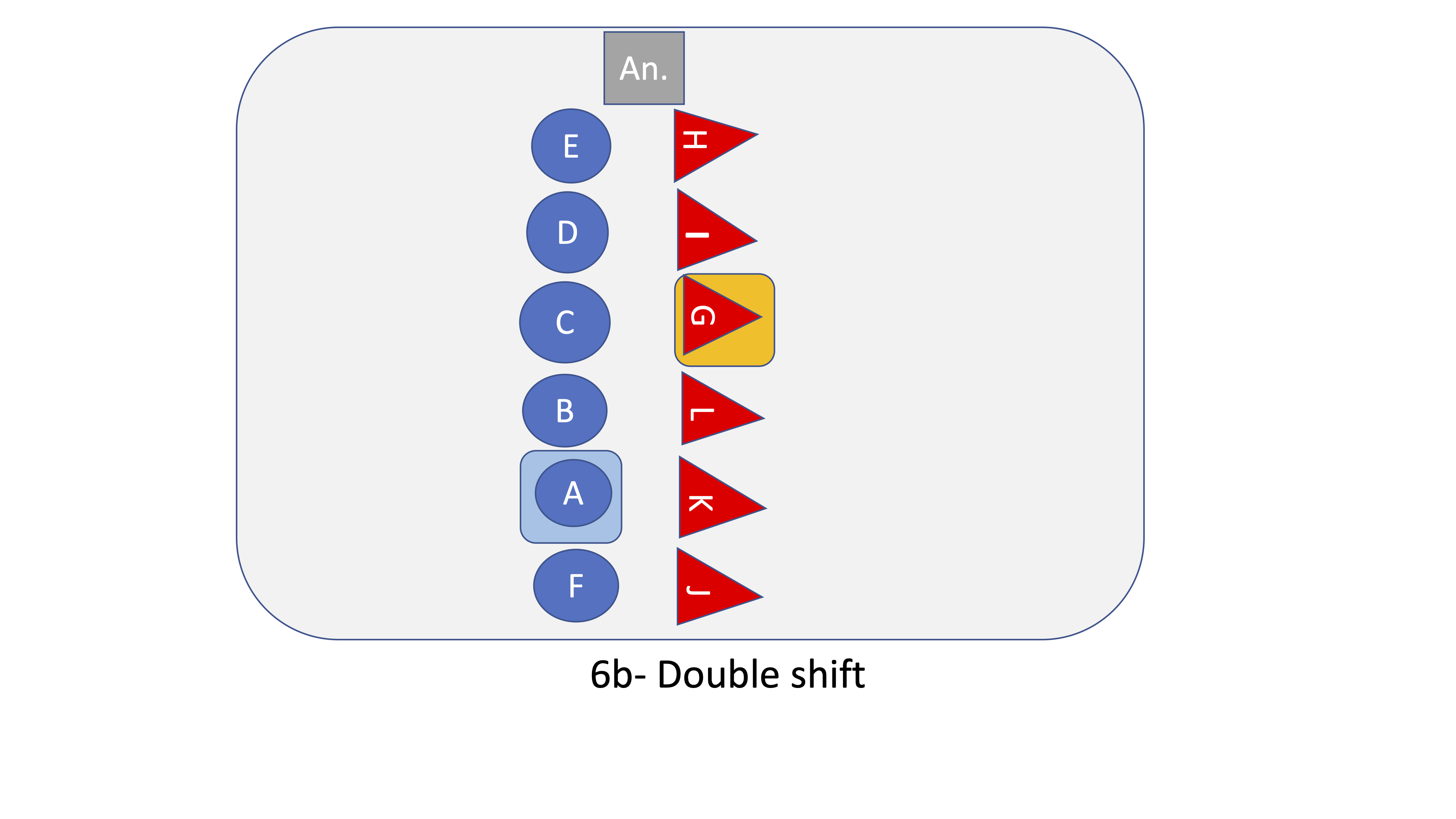

Then a "double shift" can take place, in which each participant has a conversation partner. (see step 6b).

2.1.7. From oral to written expression

After this verbal encounter, the trainer can propose a writing exercise in sub-groups of three or four participants. The task will be thematically related to the previous encounter and the participants put themselves in roles that correspond to the task (e.g. as the protagonists making an entry in their diary, or sending a mobile phone message to a friend or colleague, or as police officers drafting a report, or as journalists writing an article about the imaginary persons or their encounter).

STAGE 5

2.1.8 - The reflection phase

Some linguistic correction takes place directly and spontaneously in stages 2 to 4. This sometimes leads to questions from the participants about the corrections supplied. As far as possible, the trainer lets the group form their own hypotheses and discover the regularities of the language themselves first, so that their solution corresponds to the level of knowledge of the participants. If the trainer has the impression that an explanation or a grammatical rule would make sense or be more economical in order to avoid a repeated mistake, she gives the necessary explanation. Here too, she follows the participants instead of leading them with pre-planned grammatical programming and ready-made solutions.

2.2. The consideration of dramaturgical aspects when selecting a text

In addition to the techniques of projection, identification and association, images or texts also serve as an impulse for a dramaturgical situation. We would like to illustrate this with the help of a literary text, The Return of the Prodigal Son by André Gide.

This text allows us to illustrate the two main dramaturgical criteria that we take into account when choosing a text or an image.

The dramaturgical criteria for the selection of a text

Two main criteria make it easier for us to choose a text that can stimulate the participants' desire to express themselves: The dramaturgical criteria, i.e. The presence of dramaturgical forces and The principle of resonance.

The presence of dramaturgical forces is illustrated clearly in the text by Gide, since it is the dialogue between two brothers, the older brother as a representative of order, tradition, norm ... and the younger brother, who among other things seeks the freedom and joys of life ... This dialogue symbolizes two conceptions of life.

The potential of resonance. In order to awaken the desire to speak, it is important that the participants feel addressed by the text. It is about discovering the inner resonance that such a text can evoke in the participants through its symbolic scope, so that they feel addressed and their desire to express themselves is aroused. Therefore, we ask teachers who intend to use tests in their classes to search for the themes that the text contains, as it is their symbolic scope that will enable the participants to resonate with the subliminal topics and stimulate their desire to react and express themselves in the group.

The searching for such themes also enables the trainer to prepare certain activities or set the course of the exercise based on the potential resonance of the participants. This also allows for a variety of possible set ups and/or activities.

The search for topics for a group of teachers in training

The participants form groups of three or four. The trainer distributes the text to each participant. She asks the participants to read the text for themselves first and to write down the themes addressed in the text. Then they collect the themes in the sub-groups of three and complete their suggestions with suggestions from the others. An exchange in the whole group then takes place.

To illustrate, a selection of the topics mentioned in a PDL teacher training group:

Sibling rivalry / sibling dispute / place in the family / inheritance in the family / legacy / continuity of family values /identity / inside (protection) -outside / staying - leaving / security and protection in the house vs. insecurity outside / dependency / order / security vs. Freedom / insecurity / discipline vs. adventure / holding on vs. letting go / security within borders (protection inside) and taking risks / adventure and danger outside) / conflict between tradition and modernity / order and discipline vs. Freedom and Adventure / Restriction / Setting Limits vs. Taking risks / Older brother: mouthpiece of order, law / guardian of tradition, dogma / The know-it-all: The big brother knows the rules better than the father himself / Fixed norm of religion vs. own thinking / church vs. free opinion / search for the truth / tolerance for other ways / power of the victim / function of the victim / everyone's opinion / try to convince others / forgiveness / arrogance / not listening …

I use this text as an example due to its variety of topics that are not necessarily noticeable when read for the first time.

A text that contains numerous thematic resonance options offers more opportunities to awaken identification, distance or reaction processes in the participants.

The presence of dramaturgical forces represented by each of the two brothers and the variety of obvious or latent themes that enliven this text suggest that it fulfils the requirements to awaken participants' desire to express themselves; the participants can identify with or react to the brothers and the themes.

The reception of the text is very cultural. I have used this text several times at the Stages BELC in France, where participants came from different countries, e.g. the French tended to identify with the prodigal son, while participants from other cultures had more sympathy for the older brother as representative of the law and order. The perception of the topics is therefore not universal, but also cultural.

It is then up to the trainer to approach and access this text and its dramaturgization so that the text can be experienced from within. This dramaturgization is stimulated by the power of the existing dramaturgical forces and by the high potential of resonance with the participants.

To sum up

Dramaturgy is one of the ways that promote the acquisition of a foreign language.

The above-mentioned dramaturgical principles enable the progress of new exercises to be structured better and provide important criteria when selecting documents.

The dramaturgization, among other processes that we use in the context of PDL, helps to acquire the language through experience. It promotes a participant and group-oriented pedagogy, i.e. it stimulates an individual and spontaneous expression of the participants. This personalized language enables a direct relationship between the speakers and the foreign language, which increases retention, assimilation of the foreign language and motivation. It observes some of the methodological principles of language dramaturgy: following instead of leading, proposing instead of imposing,accompanying instead of directing... and it illustrates one of the possible paths that a Pedagogy of the Way can take; in other words, a Pedagogy of Being.

© Bernard Dufeu, 2019.

Translation: Robert Zammit

[1] See: Pedagogy and Therapy

[2] We owe the use of the masks Willy Urbain, who conducted a two-week experiment "Expression Spontanée" at the University of Mainz in 1977; this then inspired us to develop what in the end became PDL.

These masks have a protective function; they also encourage participants to concentrate on the trainer's voice and on their own. For further functions of the masks see Dufeu, 2003, 71-72.

[3] The doubling and the mirror designate at the same time techniques that are used often in PDL exercises and exercises of the first days of a PDL course (see Dufeu, 2003, 142-170).

[4] Charlotte Habersack, Angela Pude, Franz Specht (2013): Menschen. Kursbuch A2, 2. Ismaning: Hueber Verlag P. 39.

[5] Souriau, Etienne: Les deux cent mille situations dramatiques. Paris, 1950. We also owe Willy Urbain for transposing Souriau's theories into the pedagogical field.

[6] Other exercises such as "the Janus Head" assume a similar principle, but are based on a different development.

[7] The participants feel that the change in intonation is connected with a sometimes strong change in meaning. The intonation can compensate for vocabulary gaps.

[8] See for more specific explanations: Course progression

[9] In courses with specific needs, the trainer proposes situations that the participants would like to master professionally. Instead of confronting them with more or less technical texts that contain this vocabulary, they acquire the linguistic resources they want from the situation. These text types can support and continue the acquisition process as a further step; for instance, as an individual activity at home.

[10] For a detailed description of this exercise, see Dufeu 1992, S. 184-191 and Dufeu, 2003, S.188-193.

[11] As a trigger for a situation in the PDL are postures, still images, exercises from the "Expression corporelle" or from the actor tradition, mental triggers (fantasy trip, imaginary or real situations), linguistic triggers (word, sentence, idioms, sayings, texts from the Press or literary texts), visual triggers (iconographic documents) etc. used, among others based on association, identification or projection processes.

[12] We owe the use of a warm-up exercise before a main exercise to psychodrama.

[13] For a detailed description of this and other warm-up exercises that can be used for the pillow exercise, see Dufeu, 2003, 188-190.

[14] When doubling, the trainer sits behind the protagonists to provide him with linguistic support.[

[15] We think here among other things exercises from “Drama Education” in Germany and exercises from “Resources book for Teachers” at Oxford University Press or “Books for Teachers” at Cambridge University Press in Great Britain.

[16] This expression was developed by Georges Pompidou during the 1969 presidential campaign in France.

[17] Otherwise the correction suggestions take place in stage 5.

[18] We differentiate between a Pedagogy of Having which is Content and Objective oriented and a Pedagogy of Being which is Participants and Way oriented.

Bibliography and Sitography

Besse, Henri (1974): Les exercices de conceptualisation ou la réflexion au niveau 2, Voix et Images du Crédif, 1974/2, 38-44.

Boal, Augusto (19892): Theater der Unterdrückten, Übungen und Spiele für Schauspieler und Nicht-Schauspieler, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. Originalfassung: Boal, Augusto (1980): Théâtre de l’opprimé. Paris: François Maspero.

Dominguez Sapien, Natalia (2019): Macht kein (Psycho-)Drama draus! Dramapädagogik, Psychodrama, Psychodramaturgie: Versuch einer Begriffsklärung. In Stefanie Giebert und Eva Gospel (Hrsg.), Dramapädagogik-Tage 2018/Drama in Education Days 2018 – Conference Proceedings of the 4th Annual Conference on Performative Language Teaching and Learning, 23-31. https://dramapaedagogik.de/wp-content/uploads/proceedings2018/final.pdf

Dufeu, Bernard: Bibliography about PDL. Bibliography about PDL

Dufeu, Bernard (1982): Vers une pédagogie de l’être: la pédagogie relationnelle. In: Die Neueren Sprachen 81/3, 267-289.

Dufeu, Bernard (1983): Haben und Sein im Fremdsprachenunterricht. In: Prengel, A. (Hrsg.): Gestaltpädagogik. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag, 197-217.

Dufeu, Bernard (1996): Aspekte der Sprachpsychodramaturgie. In: Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen, FLuL, 25. Jahrgang, 144-159.

Dufeu, Bernard (1992): Sur les chemins d‘une pédagogie de l’Être. Mainz, Éditions Psychodramaturgie (vergriffen).

Dufeu, Bernard (1994): Teaching Myself. Oxford: Oxford University Press (vergriffen).

Dufeu, Bernard (1995): Die methodologischen Grundlagen einer Pädagogik des Seins. In: Materialien Deutsch als Fremdsprache. Nr. 40, 145-162.

Dufeu, Bernard (1996): Les approches non conventionnelles des langues étrangères. Paris : Hachette.

Dufeu, Bernard (2003): Wege zu einer Pädagogik des Seins. Mainz: Editions Psychodramaturgie (Nur beim Autor unter Wege zu einer Pädagogik des Seins zu beziehen).

Dufeu, Bernard (2006): Rollenspiel und Dramaturgie im Fremdsprachenunterricht. In Jung, Udo O.H.: Praktische Handreichung für Fremdsprachenlehrer, 4. Auflage, Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 99-105.

Dufeu, Bernard (2007): Die Bedeutung des Körpers in der Psychodramaturgie. In: Zeitschrift für Psychodrama und Soziometrie 1, März 2008,50-62.

Dufeu, Bernard (2013): Das Doppeln in der Psychodramaturgie. In Zeitschrift für Psychodrama und Soziometrie 2, Oktober 2013, 173-187. DOI: 10.1007/s11620-013-0193-x

Dufeu, Bernard (2013): Psychodramaturgy for language Acquisition. In Michael Byram and Adelheid Hu: Routledge Encyclopedia of language teaching and learning. Second Edition. 565-567.

Feldhendler, Daniel (1989): „Das lebendige Zeitungstheater- Teilnehmeraktivierung im Fremdsprachenunterricht durch relationelle und dramaturgische Arbeitsformen“ In: Addison, A. / Vogel, K. (Hrsg.): Gesprochene Fremdsprache. Bochum: AKS- Verlag, 119-140

Feldhendler, Daniel (1996): „Inszenierung interkultureller Selbst-/Fremdbilder in der Fremdsprachenausbildung.“ In: Ambos, E. und Werner, I. (Hrsg.) (1996): Interkulturelle Dimension der Fremdsprachenkompetenz. Bochum: AKS Verlag, 257-268.

Floridia, Aurora (2017) Die Psychodramaturgie Linguistique-Methode im Einzelsetting. In: Zeitschrift für Psychodrama und Soziometrie 2, Oktober 2017, 319-333.

Franz, Maria von (1979) „Der Individuationsprozess.“ In: C.G. Jung (19799): Der Mensch und seine Symbole. Olten und Freiburg in Breisgau: Walter-Verlag, 160-229.

Karnath, Hans-Otto, Peter Thier, (2003): Neuropsychologie. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag.

Moreno, Jakob Levy (1914): Einladung zu einer Begegnung, Wien: Anzengruber Verlag.

Moreno, Jakob Levy (1924): Das Stegreiftheater, Potsdam: Kiepenheuer.

Moreno, Jakob Levy (1947, 19722): The Theatre of Spontaneity. Beacon (N.Y.): Beacon House Inc.

Moreno, Jakob Levy (19541, 19672): Die Grundlagen der Soziometrie, Köln: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Moreno, Jakob Levy (1959): Gruppenpsychotherapie und Psychodrama, Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag.

Souriau, Etienne (1950): Les deux cent mille situations dramatiques, Paris: Flammarion Editeur.

Trimmel, Michael (2003): Motivation, Emotion, Kognition. Wien: Facultas Verlags- und Buchhandels AG.

Website of the Centre for PDL: https://www.psychodramaturgie.org/en/

Website of the PDL-Association: http://www.pdl-verband.com/